The new firmware

Replacing the old microcontroller with an Arduino Nano was the easiest thing

to do.

Also because I could reuse many parts of the code I already wrote for the

twin-tube counter.

So, with little effort I could have the dead-time compensation, the PC

communication interface, the conversion from CPM to mR/h and μSv/h, the

low voltage alarm, and so on.

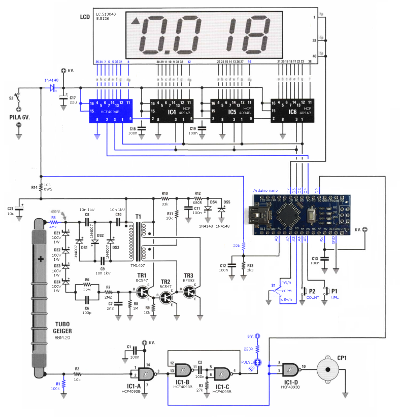

Pulses generated by the tube are shaped by IC1-A and arrive on line D2.

This line internally supports interrupt capabilities (INT0) and allows

counting all the pulses (falling edge) regardless of what the processor is

doing.

The LC513040 LCD display must be AC driven to avoid harmful electrolysis

phenomena in the liquid crystals.

Its data-sheet specifies that the frequency must be between 30 and

200 Hz.

I choose to drive it at 50 Hz by programming the microcontroller to

rewrite the four CD4094 100 times per second and invert all outputs each

time.

To fit large numbers on the four digit display, when the value exceeds 9'999,

it's divided by 1'000, the decimal point is shifted accordingly and a little

triangle in the top left corner will tell the user about the extra 1'000

factor.

So, for example, "^15.67" actually means 15'670.

The firmware (program) used for this application is available here (as

freeware): lx1407-firmware.zip

(19,704 bytes).

Il nuovo firmware

Sostituire il vecchio microcontrollore con un Arduino Nano era la cosa

più semplice da fare, anche perché mi ha permesso di

riutilizzare una buona parte del codice che avevo già scritto per il

contatore a due

tubi.

Questo ha permesso di implementare con poco sforzo la compensazione del tempo

morto, l'interfaccia di comunicazione con il PC, la conversione in CPM, mR/h

e μSv/h, la gestione della batteria scarica, e via dicendo.

Gli impulsi provenienti dal tubo, debitamente squadrati da IC1-A arrivano

sulla linea D2 che internamente supporta la funzione di interrupt INT0 e

permette di conteggiare tutti gli impulsi (fronte discendente)

indipendentemente da ciò che il processore sta facendo.

Il display LCD tipo LC513040 deve essere pilotato in corrente alternata per

evitare dannosi fenomeni di elettrolisi nei cristalli liquidi.

Il data-sheet specifica che la frequenza deve essere compresa tra 30 e

200 Hz.

Io ho scelto di pilotarlo a 50 Hz, facendo in modo che il

microcontrollore riprogrammi i quattro registri CD4094 100 volte al secondo

ed invertendo ogni volta i valori di tutte le uscite.

Per indicare numeri grandi sul display a quattro cifre, quando il valore

oltrepassa 9'999, questo viene diviso per 1'000, la virgola viene spostata e

un triangolino in alto a sinistra indica il fattore 1'000.

Così, per esempio, "^15.67" significa 15'670.

Il firmware (programma) usato in questa applicazione può essere

scaricato qui (freeware):

lx1407-firmware.zip

(19,704 bytes).